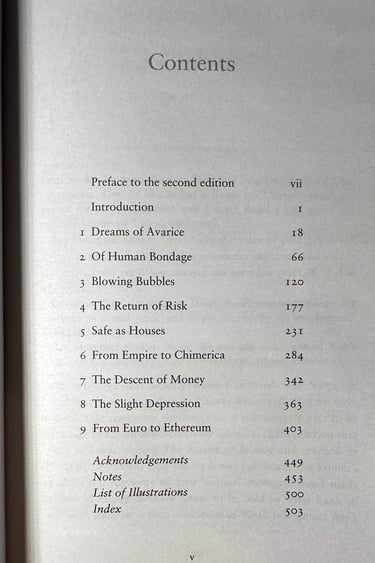

Why This Book Matters A Quick Introduction

“The ascent of money has been essential to the ascent of man.” – Niall Ferguson

The Ascent of Money by Niall Ferguson is a sweeping narrative of financial history that reveals how money, credit, and markets have shaped the rise and fall of empires, revolutions, and global systems. Rather than treating finance as a cold, technical subject, Ferguson brings it to life through storytelling linking money to war, conquest, innovation, and human behavior.

The book spans everything from Mesopotamian clay tablets to cryptocurrency, showing that financial innovation is neither recent nor neutral. Ferguson reminds us that money is not a real object it’s a shared illusion backed by trust, credit, and collective memory. Each chapter uncovers how trust, fear, and power fuel the systems we use to store and exchange value.

Niall Ferguson is a British historian known for his provocative takes on empire, economics, and global power. A senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and a prolific author, Ferguson brings academic depth and journalistic flair to his writing. His unique blend of historical insight and financial analysis makes this book both informative and highly readable.

First Impressions of Value – From Mesopotamia to the Coin

Our story begins even earlier in ancient Mesopotamia, where the earliest forms of money weren’t coins or paper, but clay tablets. Around 3000 BCE, Sumerian scribes used cuneiform marks on tablets to track debts, grain deliveries, and trade deals. Money, at its core, began as a record of trust and obligation.

As trade expanded across rivers and empires, civilizations like Babylon and Assyria continued developing this financial memory. Silver weights became early mediums of exchange, but standardization was still centuries away.

Enter Lydia, an ancient kingdom located in what is now modern-day Izmir, Turkey. Around 600 BCE, the Lydians minted the first standardized coins made of electrum a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. This innovation revolutionized trade by making money portable, measurable, and widely trusted.

Fast forward nearly two thousand years: Christopher Columbus sails west in 1492 and stumbles upon the Americas, funded by Spanish monarchs hungry for wealth. What followed was a tidal wave of gold and silver flowing into Europe primarily from the Inca and Aztec empires.

The Incas, who had never used money in the European sense, were conquered and exploited for their gold. Their riches fueled the Spanish Empire and ignited Europe's inflationary "Price Revolution."

Thus, the modern global economy was born not just in invention, but in conquest and extraction.

Money as Memory – The Silent Ledger of Civilization

Niall Ferguson opens The Ascent of Money with a powerful idea: money is just a way of remembering who owes what to whom. Societies once used clay tablets, shells, silver, and now screens.

From ancient Mesopotamia to modern markets, Ferguson argues that financial systems are at the heart of every major historical change from wars to revolutions to empires.

It’s not guns or gods that shape history most. It’s finance.

The Renaissance of Risk – Italy’s Financial Inventions and the Rise of Credit

Florence, Renaissance Italy. The Medici family played a central role in the rise of early banking and helped popularize double-entry bookkeeping, a system formalized by Luca Pacioli in 1494. But the Italian city-states gave birth to more than just beautiful art and architecture—they laid the groundwork for modern finance.

Venice and Genoa developed early forms of government bonds and credit markets to fund wars and expand trade. Merchants and states alike issued and traded debt, often backed by taxes or tolls.

The first widely used bills of exchange allowing money to be transferred across distance and time were formalized in these cities, creating a prototype for modern banking and international finance.

In Florence, merchant families like the Medici combined political influence with financial expertise. They offered deposit and lending services, maintained ledgers, and facilitated currency exchange.

These innovations made it possible to scale commerce, manage sovereign debt, and separate the act of buying from the movement of money.

“Poverty is not the result of rapacious financiers exploiting the poor. It has much more to do with the lack of financial institutions, with the absence of banks, not their presence. Only when borrowers have access to efficient credit networks can they escape from the clutches of loan sharks, and only when savers can deposit their money in reliable banks can it be channelled from the idle rich to the industrious poor.”

– Niall Ferguson

Debt became both a tool of opportunity and a source of downfall.

The financial revolution was underway.

Speculative Cycles – Euphoria, Collapse, Repeat

One of the most fascinating figures Ferguson profiles is John Law, a Scottish gambler and economist who convinced France to adopt paper money and centralized finance in the early 1700s. His creation of the Mississippi Company led to a massive asset bubble arguably the first large-scale monetary experiment gone wrong. Law's rise and fall exposed how innovation, when mixed with unchecked speculation, can spiral into national disaster.

Just as instructive is the strange timing of Bitcoin’s emergence the domain bitcoin.org was registered on August 18, 2008, just weeks before the collapse of Lehman Brothers. While Ferguson doesn’t dwell deeply on Bitcoin in this book, its symbolic timing reinforces one of his main themes: financial innovation often rises from the ashes of financial ruin.

Ferguson dives deep into famous financial manias:

The South Sea Bubble

The Mississippi Company

Tulip mania in the Dutch Republic

Each one shows a familiar pattern: excitement, speculation, overconfidence, and collapse.

Markets repeat themselves because human psychology doesn’t change.

Sovereign Finance – Bonds, Wars, and Early Insurance Innovation

The British Empire was not just built on naval power — it was built on bond markets. Britain could borrow cheaply, outspend rivals, and finance wars. Much of the funding for conflicts like the Napoleonic Wars came from its deeply developed government debt markets.

In contrast, rivals like France struggled with fiscal mismanagement and defaulted repeatedly.

Financial strength became national power.

The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 wasn’t just a military victory it marked a financial turning point. The Rothschild banking family, known for their rapid courier networks, reportedly received early news of Napoleon’s defeat. While the full extent of their market actions remains debated, their ability to act swiftly gave them a major edge in the bond markets.

As finance evolved, so did tools of security. One important innovation was life insurance, originally designed to support widows and orphans of British clergy and military officers. The Amicable Society for a Perpetual Assurance Office, founded in 1706, laid the groundwork for a more stable financial future for families. Insurance became both a moral and financial response to risk.

But empire is expensive. As Britain’s imperial reach grew, so did its debts. After World Wars I and II, the pound sterling lost its status as the world’s reserve currency, giving way to the U.S. dollar. Financial supremacy, like military power, is never permanent.

Power Brokers – Rothschilds and the Hidden Influence on Monetary Policy

Ferguson tells the story of the Rothschild banking dynasty how five brothers spread across Europe, creating a financial network faster than any government post.

But their influence was more than just logistical. The Rothschilds didn’t simply react to markets they shaped them. By moving capital swiftly between cities, financing states, and managing information flows, they had the power to influence bond yields, support governments or let them fall.

In essence, they became early architects of global monetary policy without holding any official office. Their story shows how individuals, through vast webs of trust and timely information, can quietly steer the fate of nations.

They financed wars, kings, and revolutions and in doing so, proved that information, trust, and capital could reshape the world.

Equity for the People – Birth of the Stock Market Investor

From the rise of joint-stock companies to the New York Stock Exchange, Ferguson shows how equity markets let ordinary people become investors and sometimes speculators.

But every boom has its bust.

From the Wall Street Crash of 1929 to the Dot-com bubble, each era has its own story of overreach and reality.

Real Estate Dreams – When Safety Becomes the Illusion

Ferguson devotes an entire chapter to real estate. From American suburbs to Japanese apartments, people believed housing prices could never fall.

Then came the 2008 financial crisis.

The lesson: the safest assets are often the ones we stop questioning.

Capital Without Borders – Crises That Cross Continents

The book connects crises across borders: how Argentina's default, Russia's meltdown, or Thailand's crash sent shockwaves globally.

Money moves faster than ever and so do its risks.

Cycles of Confidence – Are We Really Wiser Now?

Finance evolves, but the patterns stay the same. Innovation promises safety. Speculation creates euphoria. Crashes reveal fragility.

Ferguson ends with a challenge: to understand finance is to understand the world its past, its present, and its possible futures.

In Your Pocket, In Our History – A Final Reflection

I was fascinated by the history of money while reading this incredible book. Ferguson's storytelling not only made centuries of financial evolution understandable, but truly captivating. I’ll likely return to this book in the future to absorb even more insights. I strongly recommend The Ascent of Money to anyone interested in uncovering the often forgotten financial forces that shaped the world we live in today.

The Ascent of Money is more than a book about banking. It’s a story about us. About how trust becomes value. How fear becomes crisis. And how finance is always intertwined with power.

It reminds us that understanding money isn’t optional. It’s essential.

Because whether we like it or not, we’re all participants in the financial story of humanity.

In the final chapters, Ferguson introduces Chimerica the financial marriage between Chinese savings and American consumption. It’s a system of imbalance, where the East saves and lends, and the West spends and borrows.

Today, with the rise of digital currencies and China's increasing influence in institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and its push for a digital yuan, we may be witnessing the start of a new monetary order. The dollar may still dominate but for how long?

Understanding the ascent of money means recognizing that its journey is far from over. The next chapter may be written in code, powered by data, and led from the East.

Discovering Planet Finance: From Clay Tablets to Digital Currencies